James Squire and Pirate Life face ABAC panel

A raft of ABAC judgements released this week have brought to the fore the relationship between sports and alcohol advertising, with James Squire and Pirate Life being on the receiving end of complaints.

The first ruling by the ABAC panel was in regards to a television advert for James Squire One Fifty Lashes, broadcast on SBS during the US Open Semi Final at 8.20am.

The complainant was concerned not about the content of the ad, but rather the placement of it during a major sporting event constituting a “violation of alcohol advertising standards”, and the time it was broadcast, when, they said, children might be watching the US Open.

Brand owner Lion said it was committed to upholding the “letter and spirit of ABC and AANA Codes” and that it complied at all times with the alcohol provisions in the Commercial Television Industry Code of Practice, in that the advertisements were placed in slots expressly permitted by the CTICP. They said the advertisements were allowed as accompaniments to a sports programme on a weekend or a public holiday.

Lion also argued that the live ratings for the 2018 and 2019 US Open indicate that 96 per cent of viewers watching the tournament were over the age of 18.

The ABAC Code determines that marketing must not be directed at minors either through the style of the packaging or marketing, or through a breach of placement rules. These rules stipulate that if there are no age restriction controls on a media outlet, then the audience should be reasonably expected to consist of at least 75 per cent adults.

The ABAC panel explained that the relationship between alcohol marketing and sports and cultural events is part of a wider debate about whether alcohol companies should be allowed to sponsor competitions or teams. Ultimately, the ABAC panel said, this is an issue of public policy and therefore beyond their remit.

It did judge, however, that the James Squire advert fulfilled its obligations with regards to being broadcast during an event largely watched by adults. The panel declared that while tennis has appeal across age groups, it cannot be reasonably believed that the TV broadcast of Grand Slam tennis championships is primarily aimed at minors, and dismissed the complaint.

Snowboarding collaboration

In another sports-related ruling, ABAC passed judgement on the packaging and Instagram posts promoting CUB-owned Pirate Life’s Frontside Ale, a beer brewed in collaboration with snowboarding company Burton.

The complainant said that the advert puts snowboarding and beer in the same context, creating a link between the two which breaches the ABAC code, as snowboarding is a sport that requires high levels of alertness and physical coordination. The beer itself is named after a snowboarding trick, connecting the performance of snowboarding tricks and the consumption of beer, they said.

CUB responded saying that the “genesis of this campaign” was to draw on Pirate Life’s existing successful sponsorship of alternative sports such as mountain biking and wakeboarding.

It said that the collaboration with Burton was a “natural fit” and rejected the assertion made by the complainant that there is a link made between consuming alcohol and snowboarding in the marketing materials.

It argued that the name and advertising of Frontside were an homage to snowboarding and the associated lifestyle, citing previous collaborations including Budweiser and skateboarding brand Supreme, Union snowboarding bindings and Pabst Blue Ribbon and activewear brand Lululemon and Stanley Park Brewing.

These showed that collaborations in this space are common and well understood by consumers, it said.

CUB continued that there was nothing in the name or design which shows or implies that beer should be consumed before or during snowboarding, and iterated that none of the images shown show the consumption of beer at all, and at worst, show people finishing snowboarding (with goggles or gloves off) before turning to the beer.

However it did attempt to alleviate itself of potential blame, saying that the Burton Instagram posts were not authorised explicitly by CUB or Pirate Life, but they “draw on content created by Pirate Life and Burton in collaboration”.

Pre-vetting approval was not sought for the name, packaging or posts. ABAC said that as Burton is not an alcohol beverage company, its marketing activities are not usually under ABAC’s jurisdiction, although as the content had been created as a collaboration, CUB has a reasonable measure of control over the portrayal of its beer product by Burton.

It did say that associating the snowboarding brand with the beer is not in itself a breach of ABAC standards.

In the end the panel ruled that the packaging and product name are not in breach of the code as there is no depiction of snowboarding on the can, and none of the advertisements’ messaging implies that it is acceptable to consume alcohol before or during the sport of snowboarding. The complaint was dismissed.

Bluey Beer

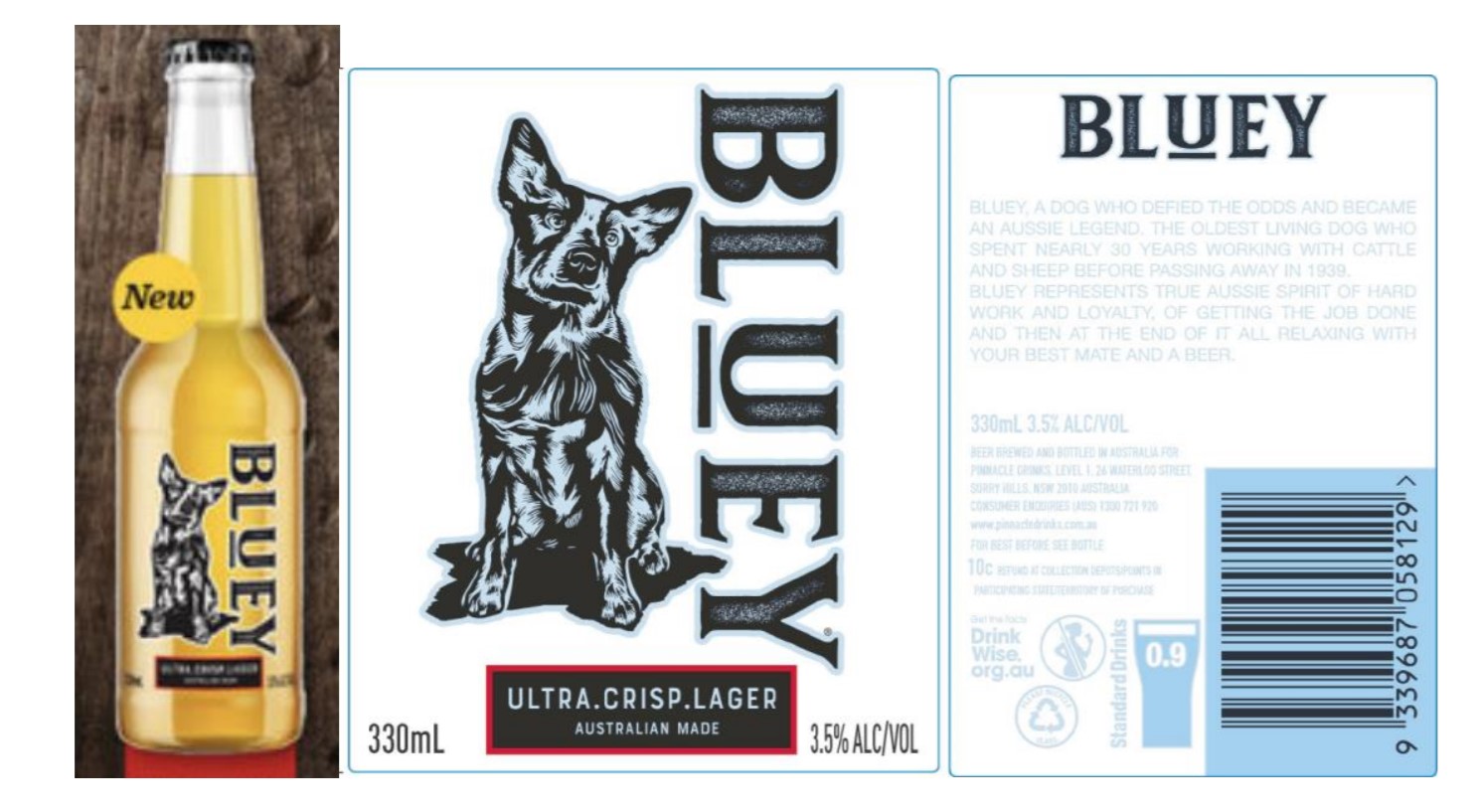

Endeavour Drinks Group’s Bluey beer brand also faced judgement from the ABAC panel, after a complainant took umbrage to the use of a dog illustration on the packaging, as well as its similarities with the principal character and title of children’s TV programme Bluey.

The concerns related to both product names and packaging of the beer, and are similar in theme to those brought against Cheeky Monkey and Hop Nation’s Jedi Juice with regards to its alleged appeal to minors.

Pre-vetting approval was not received specifically for the packaging, however collateral which included the name and images of the packaging was approved.

Endeavour, which has been a signatory of ABAC since 2013, said that Bluey was launched in October 2018 featuring a sketch of an Australian cattle dog – a revised version of the Ol’ Bluey brand which is also owned by Pinnacle Drinks.

It said that its use of a dog motif does not automatically meet the scope of a “strong or evident appeal to minors” as dogs are “generally liked by a broad spectrum of the community,” it said.

The use of an Australian cattle dog is actually less appealing to minors compared to other dog breeds due to its heritage and common use of the breed as a working dog, Endeavour argued, and highlighted the use of animals in alcohol-related marketing in relation to other ABAC rulings which the panel had deemed acceptable.

It also said that it had been using the Bluey name before the advent of the children’s TV series, that the two uses of the name are coincidental and a ‘reasonable person’ would not draw a connection between the show and the lager.

ABAC said that the term ‘bluey’ has a long history in the Australian vernacular and popular culture, highlighting many instances of the word, including a Second World War comic strip, a civil engineering company and a brand of laundry powder.

The point, the panel said, was that there was no monopoly on the use of the name Bluey. They said that the depiction of the blue heeler dog does not resemble the animated TVcharacter and it has ‘typical’ packaging for beers. The complaint was dismissed.

Two additional rulings were made with regards to a Jack Daniels brand extension complaint and bottle shop Star Liquor.

A complaint was made against the promotion of Jack Daniels-branded BBQ glaze, which stated that it was socially irresponsible to promote alcohol consumption as a Father’s Day message, that parental alcohol consumption plays a role in child abuse cases and that the promotional gifts and marketing were in the direct line of sight of children.

The complaint was dismissed with the ABAC panel stating that the products being sold were not alcoholic beverages and they have no jurisdiction over Big W as it does not sell alcoholic beverages, although the products in question are considered a brand extension for ABAC purposes.

It said the issue of government policy on the use and promotion of alcohol in various settings and for occasions was well beyond its remit. The products had minimal appeal to children, the ABAC panel ruled, saying the branding was consistent with the desire to appeal to adults rather than children.

The last was a ruling over a Star Liquor Facebook advertisement, which stated that Red Bull and Jagermeister was the “breakfast of champions” and was labelled in an image on the company’s page as ‘Heart Starter’. The complainant said it was inappropriate and could be suggesting a medical benefit from alcohol consumption.

The post was removed upon receiving the complaint and Star Liquor said they were looking at incorporating the ABAC code in staff training. They said that the price was a ‘disincentive’ to purchase as the advertised price was set at a premium – thus not encouraging rapid consumption. ABAC said it was right to take down the post as a reasonable person might consider it as promoting health benefits.